This is an article about political fusion. But it won’t seem that way for several paragraphs.

This is an article about political fusion. But it won’t seem that way for several paragraphs.

From pretty much any perspective you want to look — drama, comedy, tragedy, intrigue, farce, oddity, chaos, what if, — it’s pretty hard, among political events, to beat the 1860 Presidential election.

From a basic “what happened” standpoint, it’s easily the most unique election in American history. There were four candidates, representing three parties. One of the parties — the Democrats — had imploded at its convention in May and split into two factions. The second party — the Republicans — did not exist seven years prior. And the third party — the Constitutional Unionist — did not exist seven months prior.

The 1860 election also marked the collapse of the Presidential election system that had been devised by the Founders in 1787, and their attempt to build a system that required candidates who sought the Presidency to acquire a national following with strength in all areas of the country. None of the four candidates in 1860 were able to do this (and no single candidate for President would win a majority of the vote in both the North and South again until 1932):

The winning candidate (Abraham Lincoln, Republican from Illinois) ran on a party platform whose main plank —

The normal condition of all the territory of the United States is that of freedom; that as our republican fathers, when they had abolished slavery in all our national territory, ordained that no “person should be deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law,” it becomes our duty, by legislation, whenever such legislation is necessary, to maintain this provision of the constitution against all attempts to violate it; and we deny the authority of congress, of a territorial legislature, or of any individuals, to give legal existence to slavery in any territory of the United States.

— drew a line in the sand on the westward expansion of slavery such that his party need not bother to seek votes in the south, for none would be available. And indeed, said candidate received zero votes in nine states, and less than 3% of the vote in three others. (It’s a misnomer to say — as many people do — that Lincoln “wasn’t on the ballot” in the south. That’s not how elections worked in the 19th century; there was no ballot to get on. Citizens handed in their own “tickets” — either homemade or, more likely, cut out of a party newspaper. So when Lincoln got zero votes, it means exactly that — no one was mass printing Republican tickets in the south, and not a single individual wrote up his own.*** This will become important late in this essay). Instead, Mr. Lincoln sought only support in the North, where a clean sweep would be enough to get half the electoral votes.

The only candidate even remotely capable of beating Lincoln was Stephen Douglas (a Democrat from Illinois). He was capable of winning significant votes in the North, and his party was overwhelmingly dominant in the South. Unfortunately for Douglas, he was in a position that no viable national candidate for the Presidency has even been in, before or since: he had spent the past 3 years fighting for his political life as his own party attempted to crush him. As a Senator from Illinois and a true moderate on the slave question, he had split with the party over the question of slavery in Kansas territory, joining the Republicans in opposing the LeCompton constitution. This made him public enemy #1 among both the southern Democrats and the Buchanan administration (Buchanan was from Pennsylvania, but a pro-southern doughface), who spent the better part of 1858-1860 trying to drive Douglas to defeat in his Senate re-election battle and then the Democratic nomination fight.

When Douglas arrived at the Democratic convention in Charleston in May, he had more support than any other candidate (the Democrats accorded delegates based on state population, not Democratic support in the state, meaning the waning northern Democracy was still quite powerful in the convention), but not the 2/3 required by the party for nomination. It didn’t matter, because as soon as the platform committee refused to endorse the Dred Scot decision and promote a federal slave code for the territories, the southern delegates walked out. The convention adjourned to Baltimore six weeks later, and Douglas was nominated by a northern Democracy convention. Douglas would go on to be competitive in most of the north (winning 45%+ of the vote in many states), and marginally popular in the south (winning 10% 0f the vote in some states).

The southern Democracy reconvened their own convention in Richmond and nominated their own candidate (then-current Vice President John Breckenridge, of Kentucky). Although no fire-eater himself, he would carry the mantle for the ardent pro-slavery forces in the deep south, winning every non-border state, although often with less than 50% of the vote, as other candidates ate into his total. Breckenridge would run with some strength in the borders states, and a minimal but non-zero showing in parts of the lower North.

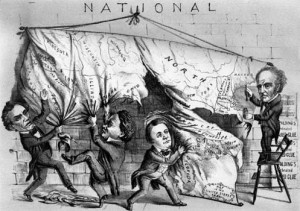

The candidate of the newly-formed Constitutional Union party (John Bell, from Tennessee, shown in the cartoon trying to hold the map together with a small, worthless, jar of glue) found his strongest support in the states — Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia — that would themselves be torn apart politically if the union were to fracture, and also would be most likely to be reduced to rubble if war broke out between the sections. Although the latter was still comical in the Fall of 1860, the former was not. And thus, while Bell was not able to win a majority of the vote in these states, he won a plurality and captured the electoral votes. Bell also won a surprising share of the vote in the deep south, competing strongly (but ultimately losing) to Breckenridge in places like North Carolina (46%) and Louisiana (40%).

And all of this is background for the main point of this article: Fusion. And why didn’t the Democrats, or all the anti-Lincoln candidates, fuse in 1860?

I suppose an explanation of fusion is necessary. The basic idea is this: when you vote President, you aren’t actually voting for the Presidential candidate. A vote for any of the candidates in 1860 was actually a vote for electors to the electoral college, just as in 2008 a vote for Obama or McCain was actually a vote for electors to the electoral college. The slates of electors (in 1860 and in contemporary times) are chosen by the parties, and are typically ultra-loyalists who will obviously vote in the Electoral College for their associated party candidate. In some states, when you vote for President, it actually says “Electors for Barack Obama” on the ballot. In other states, it just says “Barack Obama” and you have to read the fine print somewhere else to see that it’s his electors you are actually choosing. In any case, when you vote for President, you are actually voting for electors, not for candidates.

In any two-candidate race, the electors virtually cease to matter. They are simply a pass-through. But a strange possibility occurs in a multi-candidate race for the Presidency: it’s possible for electors to vote for a candidate other than the one they were pledged too, and more importantly, it’s possible for two different candidates to nominate the same slate of electors.

And thus there are two possible manifestations of fusion, both of which should seemingly be more commonplace in American politics, both in 1860 and now. The first is interstate fusion: despite being the system for almost all of American history, it’s not necessary for a party to have a convention and coordinate on a candidate prior to the election. It’s certainly helpful — you can come up with a uniform message and a national campaign is easier — but it’s just as possible to have your convention after the election, or to just narrow-down the field at the pre-election convention.

Here’s an example: the Democrats could have run Obama in most states in 2008, but run Hillary Clinton in the appalachia states and/or the deep red states where Obama had little chance. After the electors were chosen, if Clinton managed to get over the top in any states (say, West Virginia) and it represented the margin of electoral victory, her electors could have voted for Obama, perhaps in a political exchange for a cabinent position. But the point is this: a party could run 50 different candidates in 50 states, and then if the party won enough collective electoral votes to get the Presidency, they could hold their convention after the election, and choose the President there. (Assuming the electors were willing to coordinate; otherwise the election would shift to a House choice of the Top 3 vote-getters).

Now, there are ups and downs to this. First, a down: would West Virginia voters really pull Hillary levers if they knew that it was just a ploy to win Democratic votes for Obama in West Virginia? Probably not. But low-information voters might. Especially if a favored-son was running in the state. But here’s a big up: what if there’s actual regional strength differences between two prospective candidates of the same party? Or worse, what if a party has fractured into two? If two candidates from the same party run for President in the same state with different electors, they are just going to help the third candidate from the opposition party. (Think Nader in Florida, 2000).

But that’s also a perfect description of 1860! Douglas and Breckenridge and Bell were all trying to defeat Lincoln, who was the clear favorite after returns from the 1858 elections and the state elections in the summer of 1860. Why didn’t Douglas and Breckenridge (and perhaps Bell) make a deal — only Douglas run in the North and only Breckenridge run in the South, and only one of us (or perhaps Bell) run in each of the border states — and try to maximize the anti-Lincoln vote? The others will stay away and avoid “wasting votes.” Then if the combined total of their electors defeated Lincoln, they could settle it up after the election (or, if not, let it drift into the House)?

Well, there are good historical reasons. First, it was a chaotic election. Douglas thought he might be able to beat Lincoln in the North; Breckenridge had plenty of supporters who were hoping Lincoln won in order to bring on a crisis. There was no polling, so it was much harder to gauge how an interstate fusion effort would work, especially who should run in which border state, and particularly because Douglas had a slim chance of winning the Presidency outright if he won the border states and beat Lincoln in enough of the North. But mostly it was probably personal bullshit between Douglas and the Democratic party. You can’t kick a dog for five years and expect him to come rescue you when you snap your fingers, especially four months after you walked out of his coronation.

But wait, what about the other kind of fusion: intra-state fusion? This is perhaps much more important. Instead of dividing up states to run in, as described above, all of the fusing candidates instead pick the same electors in each state. For instance, for all the talk about Nader costing Gore the 2000 election, if Nader had simply had the same slate of electors chosen in Florida as Gore did, then those electors (and not Bush’s) would have won the Florida election and cast votes for the Presidency. See the point? In theory, the Democrats could have run Hillary AND Obama in every state of the union, and just had the same electors assigned to them. Again, voters might see through it if it was clear one person was going to be President, as chosen by the electoral college, but in intra-state fusion there’s really no harm on election day. You can’t lose votes by doing it, as you could with inter-state fusion.

And indeed, there were many attempts at intra-state fusion in 1860, several of which were successful.Douglas, Bell, and Breckenridge fused in New York, and were able to partially fuse in Rhode Island and New Jersey. In fact, this is how Douglas won 3 electoral votes in New Jersey; Lincoln would have probably gotten them all if Bell had used different electors than Douglas. Fusing in New York and Rhode Island did not prevent a Lincoln victory.

That’s one reason you can’t really trust the voter-level election returns in the border states and lower north in 1860. They are counts of the “ticket titles,” not the electors. (In the 19th century, a standard ticket looked like a grocery receipt, and would say, for instance, “Stephen Douglas” at the top in big letters. Down lower on the ticket, it would list the exact names of the electors, and sometimes would double as the voting ticket for other offices, and would thus list the names of a Democratic candidate for congress, state offices, and local offices. In these cases, it was one piece of paper for all those votes (thus, split-ticket voting, meaning actually physically ripping a ticket and taping in something else). Therefore, you could Douglas and Bell tickets in 1860 with the same electors written on them. Is that a voter choice for Douglas, or for Bell, or for fusion? Not clear and not discernible.)

Since the “all offices” tickets had to be produced at the geographic level of the lowest office on the ballot, it was a very decentralized system. The parties basically needed printers in every state legislative district (or at least a good distribution system into each state legislative district), since each such district would need its own tickets. So fusion could theoretically happen at very low levels (and technically could happen at the level of the individual, although it wouldn’t make sense to write Douglas on the top of your ticket and then put Bell’s electors below it. You could just write your own name at the top at that point!).

Unfortunately for the anti-Lincoln candidates, they could not agree to fuse in the key places where it could have made a difference in the outcome: in Oregon and California, where the three candidates combined for much more than 50% of the vote and thus could have prevented Lincoln from getting the electors, and in Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Indiana, where fusion would have made the races extremely close, and perhaps forced the shifting of GOP resources and the dynamic of the campaign in those states . It also would not have hurt to fuse in the border states, since that might have encouraged the belief that Douglas could win nationally, changing the dynamic of the contest. Attempts were made to fuse in Pennsylvania, but again the animosity between Douglas and the Democratic party made it extraordinarily difficult to compromise. Especially when it’s not clear Breckenridge’s team even wanted Lincoln to lose. Even stranger, Bell and Douglas could have fused in parts of the deep south and come close beating Breckenridge. Of course, Bell’s strength down there was not known (pro-union sentiment in the south was thought to be much weaker than it turned out to be during the election and subsequent secession crisis).

Of course, it’s hard to say what the consequences of a successful fusion in 1860 might have brought. The most obvious conclusion is that it would have changed nothing: Lincoln would have still won the election against a perfectly fused set of candidates, assuming fusion didn’t dynamically alter things. But if fusion could have won in Oregon, California, and one big state (either Pennsylvania or New York), all bets would have been off, as the election would have moved to the House, where the Republicans had the majority but not a majority of states, each of whom get one vote in such a situation.

What is likely, however, is that if fusion had prevailed in 1860, it might have caught on as a powerful institutional mechanism for avoiding party squabbles before an election. For all the modern talk about how much bitterness is produced and how much money is wasted in the primary season, it is surprising that the lessons of fusion have not been considered in the modern environment. Perhaps contemporary state laws regarding ballot access and campaign finance and all that make fusion impractical, but the idea of not spending millions and creating massive party animosity until after winning the election is quite appealing. One type of fusion is also illegal in many states —multiple parties putting the same candidate on two different ballot lines (and this has been upheld by the Supreme Court), and it is not clear how this applies to electors, given their strange status of not even actually being on many ballot from which they are elected.

***This isn’t exactly true. There’s some evidence that stray Lincoln voters in the south were either intimidated from handing in their tickets or had their tickets ripped up by the vote counters.

I have vivid memories of, in high school, or maybe even middle school, of flipping through my history text book, seeing the electoral map of the 1860 election that had FOUR colors on it, and thinking, wow, I can’t wait ’til we get to that one.

I’m trying to think of a modern-day scenario where such an approach might actually work and not just backfire…. having a hard time. I think the blowback from nominating a favorite son would be too great, in that it would be too transparent, even for low information voters. But who knows, maybe the Republicans in ’12 will decide to run Romney on the West Coast, Huckabee in the Bible Belt, Palin in the Plains (you can’t spell “Plains” without “Palin”), and, uh, someone in the Northeast (I think a zombie Teddy Roosevelt could take New York).

And Obama’s first name has a “c” in it, btw… unless that is some sort of 1800-Mattress-type Freudian slip on your part: “you can leave out the C for Congress!”

President’s name now spelled correctly. I like to think that I knew that for sure, and I think I did, but I’m not 100%.

I think one huge flaw of purposefully running an inter-state fusion ticket is that certain candidates — particularly anyone who thinks they will win in the House — have little incentive for their electors to compromise after the election. I see little negative about intra-state fusion — especially if the joint-electors are truly committed to the party rather than the individual candidates — except that the American people don’t really like them much weird changes, and that would certainly be one.

There’s also a huge degree of centralization now that didn’t exist in 1860. One reason fusion was so tough for Douglas, Bell, and Breckenridge was that the state and local machines had their own priorities, and the ability to enforce their will on the choice of elector slate. Fusion in New York required a coalition move among three political machines: Tammany Hall, Mozart Hall, and the Regency. That THAT was accomplished may have been the most amazing moment of the whole damn election!

Pingback: Counterfactuals, Consequences, and Election Importance | Matt Glassman