I think I’m going to lose it if I have to listen to one more person talk about how America’s fiscal problems are a “failure of the political class.” You hear this every Sunday on the major talk shows, David Brooks writes some variation of it every other week in the back of the New York Times, and most of the Washington journalistic corp not only buys into the idea, but all of them seem to think they invented the concept because they were the last ones to write about it.

I think I’m going to lose it if I have to listen to one more person talk about how America’s fiscal problems are a “failure of the political class.” You hear this every Sunday on the major talk shows, David Brooks writes some variation of it every other week in the back of the New York Times, and most of the Washington journalistic corp not only buys into the idea, but all of them seem to think they invented the concept because they were the last ones to write about it.

It’s complete nonsense. Whatever shortcomings you might ascribe to America democracy, that the Members of Congress are ignoring a massive pubic outcry is not one of them. As if somehow the problem is that all the people want nice balanced budgets and a reduced public debt, it’s just that the politicians won’t deliver it to them. Please…

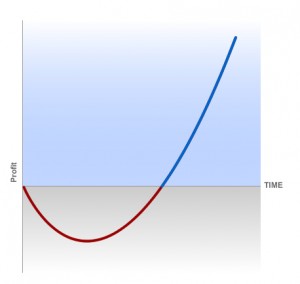

The real problem is that fiscal policy in an indebted democracy resides on a J-Cuvre. Which is nothing more than to say that the only way to achieve long-term positive results is to incur short-term negative pain. Thus the “J” in the curve (see picture). It’s just another way of explaining one of the fundamental problems democratic systems face: they are not good at long-term planning. But it’s particularly problematic when the long-term planning requires short-term pain. The classic example is moving the former Soviet bloc economies in eastern Europe to capitalism. There was no doubt that capitalistic economics would produce much better long-term growth, but the only way to get there was to set the markets free, which caused all shorts of short term pain at the bottom of the curve. Which led many voters to reject the ruling parties and reverse the liberalization. That’s a problem. In Washington (and other stable democracies) it translates to the classic political axiom: don’t produce policies that have short-term costs and long-term benefits. In fact, tend to do the opposite. So there you go.

But back to America’s political class. You constantly hear people bemoan the state of affairs that “no one in Washington will talk about raising taxes” or “no one in Washington will talk about cutting entitlements.” This may be true, but it’s not for the reason people think, some “failure” of the political class. It is because anyone who does talk about those things finds themselves not in Washington the following Congress. It’s basic natural selection. And it’s roots are with the voters, not the politicians. No one calls tax cuts without spending cuts a “failure of the political class,” and no one calls new unfunded entitlements a “failure of the political class,” but somehow the sum of those two things becomes a failure of the political class. In reality, it’s all just the political class reflecting the (short-term) interests of their constituencies.

In many ways, the J-Cuvre is just a longitudinal collective action problem (long term good vs. short-term good), as opposed to the cross-sectional version (common good vs. individual good)version that one might be more familiar with. It’s not crazy to say that these two problems are the heart of the institutional dilemma for any democracy.

The trick, of course, in any J-curve situation is to find a way to get past the bottom of the curve without the democratic electorate either (a) punishing the long-term looking politicians and/or (b) electing new politicians to reverse the policies and/or (c) both. You need to both convince the existing political class that they will not be punished, and then have it actually turn out that they are not punished. This, as you might surmise, is why autocratic states do not face significant J-curve problems the way democracies do; when there is no mechanism for reversing short-term public pain, it’s quite simple to ride out the curve until you get to the high side. You just do it. In democracies, its’s a lot trickier. Some clever mechanism have been produced in the past: establishment of things like the federal reserve to set interest rates in an environment insulated from popular election and public sentiment; placing implementation of decisions in the hands of elected officials with longer time-horizions (like the President) or no time horizon (think Supreme Court settlement of the territorial question in the 1850’s or the segregation question in the 1950’s). But for most economic issues, Congress just has to deal with it. And it’s very, very hard to deal with an economic J-Curve when you have a 2-year term.

Of course, there is another thing I hear a lot this is equally silly: that we can cut the budget deficit and reduce the debt without major sacrifice, that there are really ways to not even have a J-Curve. I hear this on the right (let’s just grow our way out it! We can just lower taxes) and the left (if we “invest” in healthcare or education or policy X then the deficit will magically disappear!). It’s more nonsense. Here’s the only way to get America’s fiscal situation in order. Choose two of the following:

1) Radically cut the budget for the military

2) Radically reduce entitlement benefits (social security and healthcare/medicare)

3) Substantially raise taxes on the middle class (and maybe the working class)

Anyone who tells you anything else is either deceiving you or deceiving themselves. All the ideas around the edges that people propose really don’t get you enough revenue or cut enough spending. Reverse the Bush tax cuts on the wealthy? Sure, but that doesn’t get you started. End the war in Iraq? It’s a rounding error. Raise the gas tax? A drop in the bucket. The cigarette tax? Useless. Uncap the payroll tax? Doesn’t even get you close. Raise the retirement age? Hardly worth the effort, unless you mean raise it to 80. Even my personally-favored, libertarian-ish suggestions (end the war on drugs; stop subsidizing farmers not to grow food) don’t get you anywhere. Do all the things I just listed? Off the cuff, I don’t think it gets you 1/3 of the way there.

And so we are stuck with the J-Curve. Figure out a way to cut the military, the entitlements, or substantially raise taxes, such that we can see the benefits within two years. That’s the dilemma in Washington.

To which I usually hear one of two responses: first, that budget deficits don’t matter. Which is true, so long as people are still willing to loan you money and you don’t mind servicing debt. Neither of those things will inevitably remain true over the next 30 years. Second, that politicians should be willing to lose their seats to make these things happen, if they were truly interested in the public good. Perhaps. But there are two problems with that logic: first, it’s not clear that the people who replace them won’t just reverse the policies. Which means that they might be out a job without even achieving any of the good. And second, ask yourself this question: is there a public policy out there that you you would personally give up your current job to achieve, with little hope of getting a similar job anytime soon?

Damn J-Curve. It’ll ruin your weekend.

Pingback: On Courage | Matt Glassman

Pingback: In (partial) defense of less democracy | Matt Glassman